Remembering New Zealand’s larger-than-life birds, taken from us way too soon.

One of the first thing I came across when visiting New Zealand a few weeks ago were towering sculptures of New Zealand’s two most famous birds, nestled in a small green area between the international and domestic terminals at the Auckland Airport. One was a giant sculpture of a kiwi. Flanking the kiwi sculpture was a bronze moa, too small to do the actual bird justice, which is what they probably would have wanted. Both of the sculptures symbolize the incredible lifeforms that call (or called) New Zealand home, but the moa represents more than just New Zealand. It represents the end of an era when our earth was obsessed with making things bigger during the last few ice ages. It represents the extremes of what is possible for nature. And most poignantly, the demise of the moa represents man’s dominance over nature.

The Auckland Airport’s moa!

So who were the moas? Moas were large flightless birds, ranging from the size of a turkey to the tallest bird ever that would have been eye level with the rim of a basketball hoop. The nine species of moas belong to the order Dinornthiformes, and were originally placed in the ratite group along with the modern giant birds of today like the ostrich and cassowary. But recent studies have found that moas are more closely related to the tinamous birds of South America, which are much smaller and can fly.

Sizing Up Moas: This sketch compares the height of the average human man (5’9” in the US) and the shortest and tallest moas, the little bush moa and the South Island giant moa (which weighed up to 550 pounds), respectively. The South Island giant moa was the tallest species of bird ever, and would have been a dominant basketball player if it had arms or wings.

New Zealand is known for its flightless birds, but moas took that trait to the extreme. They are the only group of birds to completely lose their wing bones. This shrouds their arrival on New Zealand in mystery (they obviously did not fly there without wings) and makes it likely that their ancestors were on the landmass before it split from the rest of Gondwana 85 million years ago or arrived shortly thereafter, and then proceeded to lose their wings.

Without wings, moas used their long legs to get around. The earliest arrivals to New Zealand, the Maori people who arrived around 850 years ago, say that moas were swift and agile runners and would kick to defend themselves. Their temperament seemed to be tamer, however, than modern-day cassowaries who disembowel someone every so often with a swift kick to the stomach. Although intimidating due to their massive size, the moas were peaceful vegetarians, eating grass, leaves and berries from the treetops accessible with their long necks.

South Island giant moas strut their stuff in front of New Zealand’s Southern Alps.

The giant eggs of moas had surprisingly thin shells, some only a millimeter thick. Only around 30 intact moa eggs survive to do this day.

When looking at such a large animal, one cannot help but wonder what kind of sound it made (we all think about T. rex’s roar right?). Thanks to the fossilization of some moa bones from their throats, moas probably sounded something like a giant swan or crane vocalizing through a megaphone, with deep, booming calls that could travel for miles. No one would call moas a James Dean because they effectively lived slow and died old. Unlike many other birds, who mature in a year, moas took around 10 years according to rings in their bones. As you may expect, moa eggs were giant, capable of being almost ten inches long and seven inches wide.

New Zealand proved to be the perfect place for the moa thanks to a lack of mammalian predators and other large herbivores. The only thing the moa had to worry about was death from above thanks to a complimentary large bird of prey, the Haast eagle that had talons the size of tiger claws. Even so, moas thrived on New Zealand for millions of years. Fossils of moas have been found dating back some 2.4 million years and would have lasted another few million years if not for the arrival of man to far flung New Zealand.

The extinction of the moa on New Zealand was caused by the arrival of humans who over-hunted the birds to extinction. According to a 2014 study taking DNA from 281 individual moa specimens, representing four moa species, the bird’s population numbers were stable for the 4,000 years preceding their extinction. The largest species, the South Island giant moa, was even seeing an increase in its population until humans arrived. There were no signs in the moa’s genetic history, like low genetic diversity, that show an animal declining towards extinction. This rapid “disappearance” of the moa, approximately one hundred years after humans arrived is the smoking gun for its extinction.

A man and his moa: Paleontologist Richard Owen, best remembered for coining the term “dinosaur” and helping start the British Natural History Museum, was sent a leg bone fragment from a strange New Zealand animal in 1839. The bone’s light weight perplexed Owen, who suspected it to come from a mammal because of its large size. After four years, Owen concluded that it was in fact from a giant bird and named it Dinornis. After skepticism from much of the scientific community, Owen was ultimately proved right when vast amounts of moa bones were found throughout New Zealand. Today his bust sits beside a moa skeleton cast at Auckland’s War Memorial Museum.

The moa is not the only large animal to be wiped out by humans over the last few thousand years. In fact, it effectively bookends this trend of megafaunal (large animal) extinction that began around 13,000 years ago. Species like mammoths, sabertooth cats, giant marsupials in Australia and ground sloths all disappeared over the last 10,000 years as humans began to spread around the world. In most cases humans were not the only cause. Several ice age species were also dwindling due to climate change as the earth warmed, and human hunting helped wipe out a struggling species. The trend of human impacts on megafaunal extinctions are painfully clear on islands as species began to go extinct from island to island upon the arrival of humans. The extinction of the moa 600 years ago ends this series of megafaunal extinction that saw some of the biggest terrestrial animals since the dinosaurs go extinct.

Moa Skulls: Moas were all part of the Order Dinornithiformes but split into two different families: the Dinornithidae family and the Emeidae family. The moas that Owen named Dinoris are part of the first family and include two species: the North Island giant moa and the South Island giant moa (second from left). The other seven smaller species (including the other three skulls pictured here) are from the Emeidae family and are from both the North and South Islands. This sketch is based off of skulls at the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

But the moa lives on in the imagination of New Zealanders and people from around the world. The giant bird would have been a sight to behold in real life, making the ostrich look mundane by comparison. But perhaps its early demise saved it from some of the indignities faced by its living relatives. If it had survived to see European settlers in New Zealand, it just as likely would have gone extinct from hunting. Many of New Zealand’s other birds are not doing too well today, from the kiwi to the kakapo, thanks to invasive mammals and habitat loss. If the moa had somehow survived two waves of human hunting, how much of its habitat would be left today? In addition to hunting animals, humans also find other ways to exploit large animals for economic gain. With larger eggs and greater size, the moa would have probably replaced the ostrich in zoos and farms.

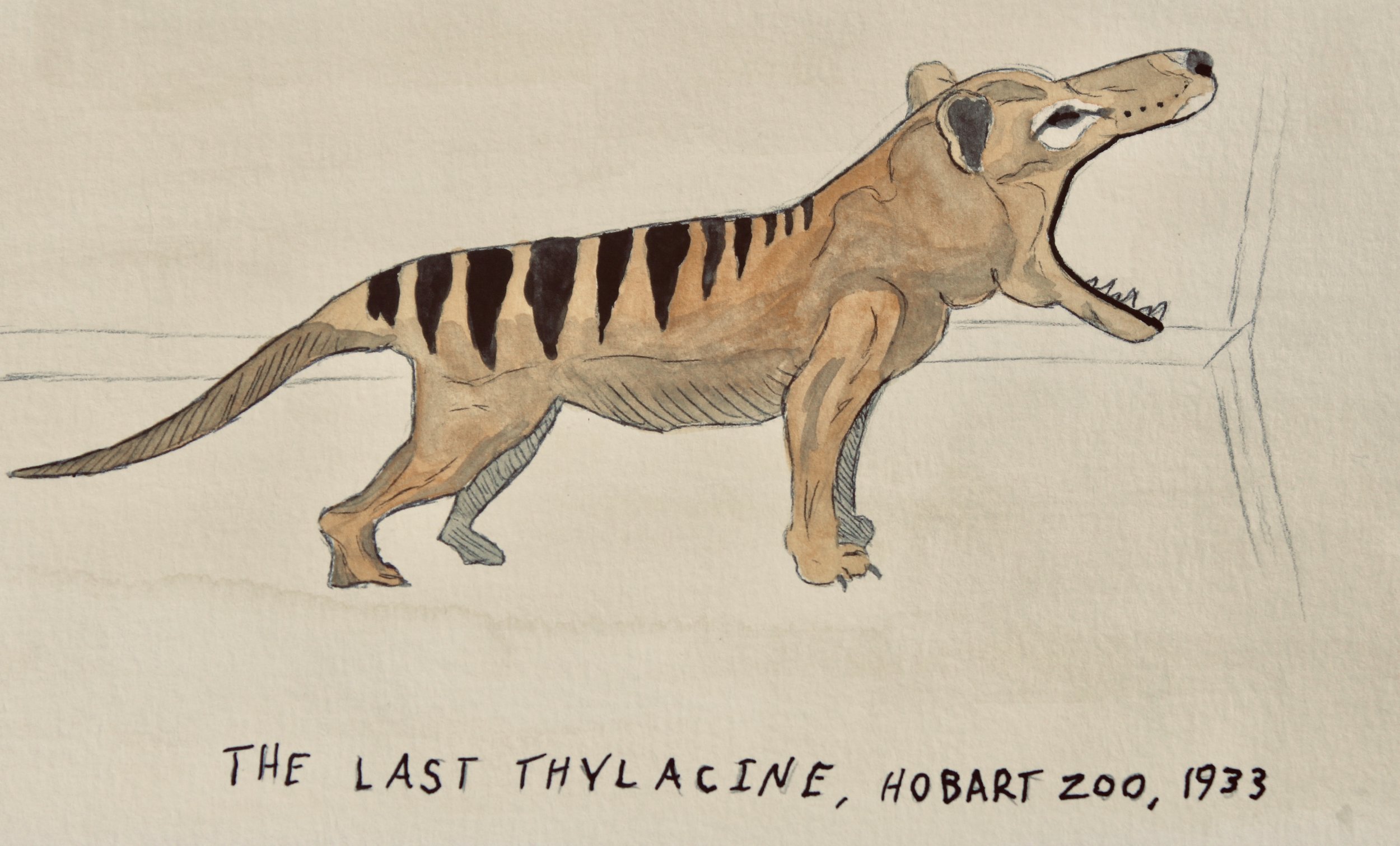

Mummified moa: This painting is based off of a mummified foot found inside a cave at Mount Owen. The preservation of this foot, which dates back some 3,300 years, is so great that some muscle and sinews are still intact along with the creature’s scaly skin. This foot once belonged to the upland moa, which was the last species to go extinct around 1500. Among the smallest of moas, the upland moa preferred to live in the cold, alpine environments of the South Island.

The moa is gone forever, which is an existential bummer. Moas are often mentioned in the de-extinction debate as a species that could be revived since their extinction fits the date range for relatively intact genetic material. This material has been left behind in large amounts of fossils and mummified remains. But that is a discussion several decades away, if ever. For now we should just take solace in remembering New Zealand’s giant moas, the last true giants to roam New Zealand’s primeval forests.

Never forget the moa! Picture taken at the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

All photographs and art by Jack Tamisiea.

Related Articles

Sources:

The Auckland War Memorial Museum moa displays

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2014/03/why-did-new-zealands-moas-go-extinct

http://extinct-animals-facts.com/Extinct-Animals-List/Extinct-Moa-Bird-Facts.shtml

http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/upland-moa