Exploring the vast stretches of the ocean’s abyss where sea serpents, giant predators and terrifying fish abound.

Although submersible technology is extremely advanced, I still like to envision an old, rusty submarine slowly descending into the abyss.

Deep below the surface of our ocean lies a giant expanse of perpetual darkness. Rays of light begin to fade rapidly the lower you go, swallowed up by the seemingly empty blackness of the abyss. This eternal darkness encompasses 95% of the living space on earth, and may at first seem lifeless. But the abyss is full of creatures who seemingly belong to a strange world. Thanks to the crushing pressure, freezing temperatures and lack of light, they essentially do live on a different planet.

The abyss begins at around 650 feet below the surface, where light begins to be snuffed out and the temperature free falls. At 13,000 feet, the only light that one may stumble upon is produced by the strange creatures who call this place home. Though many are small, they are studded with mouths full of jagged teeth and jaws that detach to hold on to the rare meal that swims too close. But not all animals down here are small, as some of the largest animals in the ocean, who have inspired centuries of nautical mythology, also lurk in the abyss.

Due to its inhospitable nature, it is often said that more is known about the surface of other planets than the deepest reaches of earth’s oceans. But new technology in deep-sea submersibles are making earth’s last vast unexplored wilderness known to us. The creatures down there have always interested me because of not only their frightening look but also because of the remarkable adaptations they use to thrive in places almost as inhospitable as space. In this piece, I will look at some of the scariest and strangest creatures who exist far below the waves. Venture with me into the abyss!

The Spectacular Oarfish

For centuries, sailors have spun fanciful tales of fearsome sea serpents lurking in the vast unexplored oceans in the emptiness on maps. Sea serpents and similar sea monsters were often thrown into maps of antiquity as filler for the unknown. Perhaps the sea serpents of myth are not quite as mythological as many think.

The giant oarfish (Regalecus glesne) is the world’s longest bony fish and very serpentine in shape. They can grow up to 56 feet and weigh up to 600 pounds, already a fearsome size before factoring in any of the exaggeration that seems to accompany any good fisherman’s tale.

The name oarfish comes from their long pectoral fins which look like oars. Occasionally they are called rooster fish because of large red fins that protrude out of their heads. Their massive size may seem fearsome, but in reality, oarfish only eat plankton and lack real teeth. They usually hang out around depths of around 3,300 feet, in an area of constant dim darkness towards the beginning of the abyss. If you were to come across one here, there is a good chance it would be swimming vertical to catch the most possible plankton using their flimsy teeth-like structures called gill rakers.

Oarfish have adapted to life down here, eschewing scales for a silvery coating of a material called guanine. This helps them deal with the high pressure deep in the ocean. Their body is also apparently very gooey, according to fisherman who occasionally catch them as accidental bycatch (and finding out they are quite inedible). Besides the rare accidental catch, oarfish are very cryptic creatures and only come close to the surface when they are stressed and near death.

They can also be pushed up by storms or strong currents, which is why they are seen as harbingers for earthquakes in Japan. This seemingly outlandish claim may have some basis, as earthquake researchers have found that deep-sea fish are more sensitive to tremors at active fault-lines. In 2013, two oarfish washed up on California within one week, an incredibly rare occurrence. It offered marine scientists a unique opportunity to study the peaceful and enigmatic sea serpents of the abyss.

The ghastly and bleached remains of an oarfish (center) embalmed in ethanol at the Natural History Museum in London.

Cock-Eyed Squid

Joining the oarfish in the eternal twilight zone that stretches from 660 feet to 3,300 feet is one of the strangest creatures you will ever come across in the deep. The cock-eyed squid’s (Histioteuthis heteropsis) remarkable set of eyes help it multi-task. It is always on the lookout for a meal while steering clear of becoming one itself.

Although both of its eyes start out at the same size, the left eye rapidly grows and eventually becomes tubular and bright yellowish-green. The right eye remains small and dark. This asymmetrical set of eyes puzzled scientists for a century. Mismatching eyes is strange, even by the alien standards of the abyss.

The mismatched eyes of the deep-sea cock-eyed squid.

But scientists from Duke University cracked the code in 2017 by observing the squid in its deep Monterey Bay habitat. The squid swims upside down, keeping its giant left eye facing up while its small right eye stares down into the abyss. This helps the squid look two places at once, scanning for the shadow of potential predators above them and searching for bright bioluminescence against the pitch black backdrop below them. The left eye’s increased size helps it see shadows more clearly while the study found that increasing the right eye would not help the squid discern bioluminescence any better, which is why it stayed small.

The cock-eyed squid is a great illustration of how the deep ocean alters eye evolution. Many creatures develop their eyes to only see bioluminescence or only see ambient light. The cock-eye squid chose both. Animals in the abyss will go to great extremes to survive in the dark.

Pacific Viperfish

Battle of bioluminescence: a deep-sea shrimp spews out bioluminescence fluid in an attempt to escape from the toothy jaws of a Pacific viperfish.

Some of the most fearsome creatures lurking in the abyss are viperfish. The fish is named for the large fangs that jut out of its wide-gaping mouth. While it may look like something out of a nightmare with its scary teeth and cold, dead eyes, it looks a lot scarier than it actually is to us. The Pacific viperfish (Chauliodus macouni) is the largest species, but usually only grows to a measly foot long.

But in the abyss, they are as terrifying to anything that is attracted to the bright lights protruding down its side and belly. But these bioluminescent lights are also used for a variety of purposes to help the viperfish survive in the abysmal dark (they go down to around 16,000 feet below the ocean’s surface). The lights warn foes, help the solitary viperfish find mates, and, of course, attract crustaceans and small fish to a quick and toothy end.

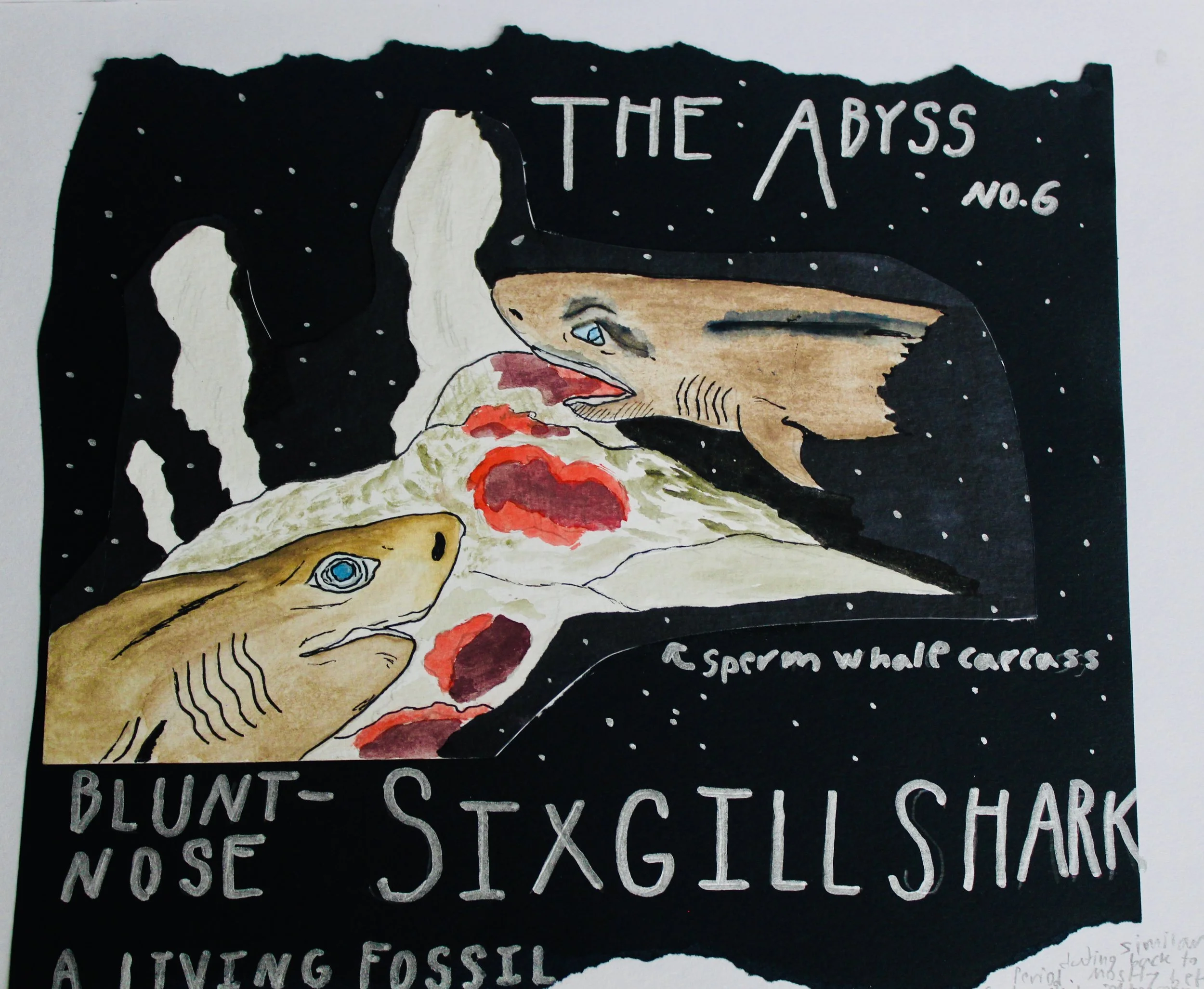

Bluntnose Sixgill Shark

One of the top predators in the abyss is this behemoth of a shark, which also happens to be a living fossil lurking several thousand feet below the ocean’s surface. The bluntnose sixgill shark (Hexanchus griseus) has a body form straight out of the Triassic Period, some 200 million years ago. Its namesake traits of a rounded nose and six gill slits, along with a single dorsal fin and broad, saw-like teeth, are all traits most modern sharks moved on from millions of years ago. For example, most modern sharks only have five gill slits.

During the day, the shark hangs out around 6,500 feet below the surface along the fringes of continental plates throughout the world, from Alaska to New Zealand. During the night it moves up closer to the surface where it feeds under the cover of darkness. It eats just about any fish it comes across, including other bluntnose sixgills, and could strike out of the darkness at any second.

The descent of a dead whale carcass is a boon for these sharks, who gather over the large mound of decaying flesh like vultures, violently ripping mouthfuls of flesh. The descent of dead material from above is one of the key food sources at the ocean floor as biological productivity dramatically drops along with the disappearance of light. The continuous shower of white organic detritus particles is aptly called marine snow (it is the white specks seen in several of the paintings in this article).

A pair of bluntnose sixgill sharks arrive at a decaying whale carcass right before the feeding frenzy commences.

Unfortunately like many sharks today, bluntnose sixgill sharks are in danger because of human hunting. The large shark is fished both commercially and caught accidentally as bycatch. Because of its cryptic existence in the deep, it is currently impossible to say just how big the decline in its population has been.

Relics From The Abyss

Some frightening denizens of the deep (left to right): tentacle and beak from a giant squid, female anglerfish below her male “companion”, and the infamous cookie cutter shark.

The collection of specimens above are based on real specimens from the Natural History Museum in London. Because of their various adaptations for inhospitable habitats, most of these species can never be displayed in aquariums and when they do end up near the surface, they are usually dead or dying. The best way to glimpse the creepy collection of deep-sea animals is often through an appropriately creepy medium: collection jars filled with unsettling yellowish ethanol, deep in the storerooms of natural history museums everywhere. A little bit about each species above:

Giant squid

If you thought the oarfish or bluntnose sixgill had intimidating size, the giant squid’s staggering proportions blows them out of the water. They even inspired the legendary kraken of mariner tales of old. The world’s largest mollusk is the length of a school bus and has been found to weigh nearly a ton. It is one of the best examples of deep-sea gigantism, where invertebrates down in the abyss are much larger than their shallow-water relatives, likely due to the crushing pressure and freezing temperatures.

Like most denizens of the deep, the giant squid is very enigmatic and little is known about the elusive giants aside from what washed-up carcasses can tell us (pictures below). It was not until 2004 that a live one was photographed, and in 2006 a living giant squid, a “small” 24-foot live female found off of Japan, was captured for the first time.

Above: the giant squid in the Natural History Museum’s collection is over 28 feet long, on the smaller side for these creatures, and was accidentally caught over 700 feet below the ocean’s surface. The DNA of this specimen was key in determining that there is only one species of giant squid. The third picture shows the fearsome hooks it uses to latch on to prey with its feeding tentacles.

Besides the size, giant squid also have some fearsome features that make them the kings of the very deep. They have proportionally large eyes (up to 10 inches across and the largest in the animal kingdom) that help them find prey in the pitch black. They have eight arms and two longer feeding tentacles to wrangle prey into their beaked mouths. They eat anything, including smaller squids, and might even hunt small whales.

The giant squid’s corresponding giant eye from a specimen at the Queensland Museum in Brisbane.

Anglerfish

One of the most famous fish in the deepest stretches of the ocean, the aptly-named anglerfish, uses a lighted lure to entice fish swimming in the eternal night of the deep-sea. Although females usually only grow to about 8 inches, that is titanic compared to males. The life of a male anglerfish is not one of excitement, as they are reduced to a tiny parasitic stub attached to the female. The male gets to feed from the female, while the female does not need to worry about finding a mate with an attached “sperm-bank”. It is a win-win in a very harsh environment. The lure that attracts fish to the female’s toothy maw is actually an organ that contains millions of light-producing bacteria.

The sad existence of the male anglerfish, a parasite whose dragged everywhere by his lady for reproduction sake. Photo taken at the Natural History Museum in London.

Cookiecutter shark

When we think of the fearsome jaws of a shark, we often conjure up the gaping jaws of the great white. But the cookiecutter shark is infamous for its circular jaws and serrated bottom teeth that cut perfect, cookie cutter-like holes into its unsuspecting prey. It uses suction to attach to larger fish and then rotates its body to pop out the circular plug of flesh, scarring everything from marlins to dolphins and seals. Thankfully it usually hangs out below 3,200 feet during the day, far away from human swimmers. It uses its green eyes to filter light in the darkness.

What fearsome teeth you have: the cookiecutter shark’s trademark rows of flesh-slicing teeth. Photo taken at the Natural History Museum in London.

Hope you enjoyed this deep dive into the abyss. Stay tuned for the second installment highlighting more of the frightening, oddball creatures that call the deepest, darkest reaches of the ocean home.

All photographs and art done by Jack Tamisiea.

Sources:

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/hexanchus-griseus/

https://www.livescience.com/57856-mismatched-eyes-help-cockeyed-squid-survive.html

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/10/131022-giant-oarfish-facts-sea-serpents/

https://ocean.si.edu/ecosystems/deep-sea/deep-sea

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/g/giant-squid/

https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animal-guide/fishes/deep-sea-anglerfish

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/isistius-brasiliensis/