A Rothschild giraffe takes a stroll in its outside enclosure on an unusually warm December day at Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo.

2019 was a momentous year for me with my studies abroad and the launch of Natural Curios. I lived on the other side of the planet for five months in Brisbane, Australia, which spurred me to start writing this blog about the natural world’s curious nature, which was on full display during my travels around Australia and New Zealand. After a year of exploring why Australia’s koalas and monotremes are some of nature’s most curious creatures, how climate change is threatening both Queensland’s flying foxes and Grand Teton National Park’s glaciers and how a giant fossil sea monster blasted out of the outback with dynamite ended up at Harvard, I wanted to dedicate an article to highlighting some of my favorite photographs from this past year. I was lucky enough to explore the world’s largest coral reef and some of the oldest rainforests in the world. I climbed on top of volcanoes and encountered wild parrots in the snowy Southern Alps. From Australia to New Zealand to Chicago to Los Angeles, and some locations in between, I was able to cover a lot of ground over Natural Curios’s inaugural year. Thankfully, I always had a camera with me ready to capture whatever sparked my imagination. Enjoy my favorite photographs from 2019 and stay tuned for new articles in the next few days! Also, don’t forget to check out Natural Curios’s full photography gallery here!

Landscape

Below are some of my favorite landscape pictures from the other side of the world. These pictures comprise both iconic locations, like the Great Barrier Reef and the Sydney Harbor, and more tucked away places, like a quiet, secluded spot in the Brisbane Botanical Garden and Australia’s easternmost point at Byron Bay. My week-long sojourn to New Zealand (bottom row) provided some of the most breathtaking landscapes I have ever seen from the mist-shrouded waterfalls of Milford Sound to the black-sand beaches and soaring volcanic cliffs of Piha Beach to the public parks populated by New Zealand’s most populous residents—sheep.

Animals

These animal pictures are among my favorite from the past year and include animals from both Australia and New Zealand, as well as zoos and parks across the United States. Going to Australia, I was incredibly excited to see world-famous residents like cuddly koalas, gargantuan saltwater crocodiles (aka “Salties”) and ripped kangaroos. The creature that most caught my imagination while I was Down Under was the blue-headed, killer cassowary that disperses seeds in Australia’s primeval rainforests at the top of the continent. Back in the States, I captured such striking creatures as Indonesia’s green peafowl and Lowland gorillas. One resident of Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo particularly caught my attention. The Guam kingfisher is extinct on its native island due to invasive snakes and only staves off oblivion in a few zoos around the world, including the Lincoln Park Zoo. There are less than 100 individuals in the whole world. I also captured animals in the wild, like Southern California’s sea lions and New Zealand’s alpine kea in the Southern Alps.

Natural History

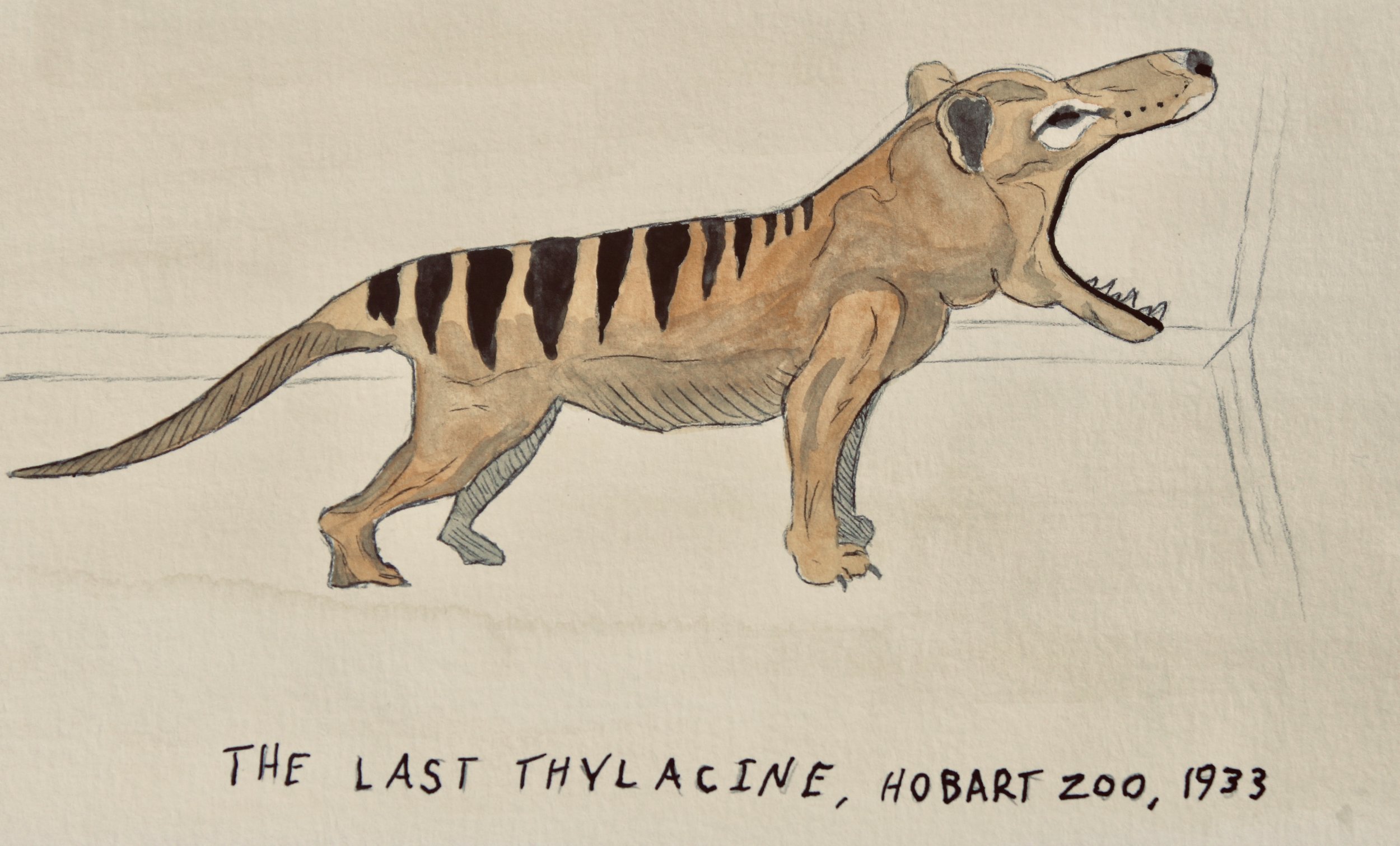

Natural history is the study that encompasses all of my favorite disciplines, including paleontology, zoology, botany, geology and environmental studies that, together, help us understand how plants and animals have interacted with the natural world over the last 4 billion years. Natural history museums are my favorite places to visit because they provide insights into the natural world through the display of a diverse assortment of interesting and bizarre specimens, like a juvenile great white shark pickled in alcohol, a dinosaur fossil with mummified skin, or a macabre wall decorated with the ancient skulls of hundreds of dire wolves exhumed from Southern California’s tar pits. Natural history displays also help us picture the distant past by assembling skeletons, like a giant predatory mosasaur or the giant Diprotodon, the largest marsupial ever. Sometimes they even give us ideas of what these primeval behemoths would look like with flesh, skin, fur or scales on their fossilized bones, like the Australian Museum did with its Diprotodon model. Only at natural history museums can you take in the scale of a pygmy blue whale skeleton and feel the explosive power palpable in the split second before an inland taipan, the most venomous snake on earth, strikes a rat. The tuatara picture is the only picture of something that is still alive, but even it offers a look deep into the earth’s past as it represents the last vestige of a whole order of reptiles (bottom row).

Cityscape, Architecture and Miscellaneous

From Sydney’s bustling fish market to Brisbane’s skyline glistening in the late afternoon sun, there were a few of my favorite pictures this year that I could not fit in the three categories above. Among them were several glimpses of the splendid gothic architecture of Australia’s Saint Mary and Saint Patrick cathedrals in Sydney and Melbourne, respectively, and the more subdued St. Peter’s Anglican Church in Queenstown, New Zealand. Queenstown’s soaring peaks also provided an intriguing backdrop for ornate grave stones. The one benefit of a mostly rainy week in Auckland were the wonderful rainbows that would spring up throughout Auckland’s bustling port, giving the cranes and barges a magical quality. And I could not resist putting a picture of one of Steve Irwin’s iconic saltwater crocodiles moving back into its enclosure after a show at the Australia Zoo.