The coelacanth and the depths forgotten by time

Descend into the past to meet the ‘vampire squid from hell,’ ghost sharks and a fish from the age of dinosaurs that came back from the dead. Enter the primeval abyss if you dare!

When we first ventured into the otherworldly darkness of the deepest depths of our oceans, we were greeted by a collection of monsters of mythic proportions thriving in the cold abyss. Immense oarfish that inspired sea serpent lore swam around us as giant squids used their tetherball-sized eyes to filter light from the perpetual blackness a few leagues below. As we prepare to return to the abyss we will again be greeted by alien creatures from a different world. However this different world is eerily similar to the mysterious oceans that covered earth tens of millions of years ago.

Before we descend, we need to clarify what a ‘living fossil’ really is. Although coined by Charles Darwin in his landmark On the Origin of Species to describe animals that have remained relatively unchanged in places with little competition, the term has frustrated scientists when used too loosely. To call something a ‘living fossil’ does not mean that creature has not evolved in millions of years. It is merely saying that the creature has retained many of the beneficial traits that made its ancestors successful millions of years ago and looks superficially similar to its fossil relatives. A coelacanth today is not the same creature as a coelacanth that swam in the ocean 66 million years ago no matter how much they may look the same.

Many of these ‘living fossils’ reside in the deep sea, preserved in a perpetually dark habitat where the traits that made their ancestors successful never went out of style. The harshness of the deep sea environment has remained relatively unchanged over the eons, so it acts like a time capsule to the primeval seas of the past.

Now that the definitions are behind us, it’s time to fasten the hatch and descend into the abyss, watching the light quickly fade as we descend back in time.

Vampire Squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis)

In the deep sea, things are often not what they seem. A playful light bouncing around the darkness is often attached to a gaping set of jaws, waiting for something to get too close. With a terrifying appearance that spawned a scientific name that means “vampire squid from hell”, one would assume that the vampire squid is a bloodthirsty squid lurking in the abyss. In reality, it is neither a fearsome vampire nor even a squid for that matter.

Residing half a mile below the surface, the vampire squid has to get creative with how it finds and consumes food. Instead of sucking blood, it feeds on marine snow, particles of dead plankton and algae that descends from the upper reaches of the ocean. Using a series of finger-like spikes down the inside of the vampire squid’s tentacles, this marine snow is gathered and pushed toward the creature’s beaked mouth (even though it is not a vampire, it still has a fearsome bite). When startled, the squid flips its arms inside out and hides within the cloak-like webbing between each arm.

Peeking under the cloak: Although these arms may look creepy, the hair-like projections are just used to collect and funnel food towards the vampire squid’s mouth. This model is at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C.

The vampire squid is a remnant from an ancient group of cephalopods (a group of mollusks that includes octopus and squids) that prospered in the oceans while dinosaurs ruled the land. Like octopus, the vampire squid has eight arms. However it also has two long tentacles that octopus lack. The vampire squid is found worldwide in tropical and temperate waters in almost complete darkness (to the envy of other vampires). It occupies its own taxonomic order as the last vestige from a once powerful cephalopod lineage, making it a true ‘living fossil.’

Giant Isopod (Bathynomus giganteus)

Keep the submarine hatches fastened as giant isopods are on the prowl!

Imagine coming face to face with a pillbug relative at the bottom of the ocean some 7,000 feet down. Only this monster is almost 3 feet long and has four sets of jaws that helps it voraciously rip decaying flesh off of dead animals that have fallen from the ocean above.

Giant isopods, found in the Indo-Pacific from Japan to Australia and the Gulf of Mexico, are the largest in a family of deep sea crustaceans. Although they are insatiable feeders on the carrion that sinks down into the abyss, they can go up to five years without eating. Their incredibly low metabolism helps them survive when food is scarce.

Giant isopods and hagfish ravish the descended carcass of a dolphin. Model located at the Melbourne Museum.

Similar to cats, isopods have a reflective layer at the back of their compound eyes that bounces light back through the retina, maximizing the ability to see in the dark. Even so, giant isopods most often use their antennas to help guide them through the abyss.

Giant isopods are a great example of abyssal gigantism as they tower over their two inch terrestrial pillbug relatives. Some hypotheses for why deep-sea creatures are often much larger than shallower water relatives is the colder temperature, higher pressure and reduced predation. The giant isopods’ ancient appearance and similarity to fossils found in Japan dating back to 23 million years ago make this terrifyingly large pillbug another ‘living fossil’ ambling around the abyss.

Deep sea gigantism: A preserved giant isopod dwarfing several of its relative isopods.

Blue Chimaera (Hydrolagus trolli) and its Relatives

A pale, ghostly shape slowly swims across our submersible’s window. It turns a sickly green eye to us and you are suddenly face-to-face with a ghost. Or a ghost shark that is.

The ghost shark, or blue chimaera, is neither a ghost nor a shark. The chimaera group as a whole, which also includes oddball residents of the abyss known as ratfish, rabbit fish and elephant sharks, are close relatives of sharks, possessing a similar body made out of cartilage (instead of bone) and sensory organs in their snouts to find prey. But the similarities are few as the last common ancestor between sharks and chimaeras swam the oceans some 400 million years ago. Instead of an endless amount of sharp teeth, chimaeras have flat teeth plates for crushing prey with hard shells. They defend themselves with a venomous spine on their dorsal fin.

In 2017, this ancient lineage of fish was finally slightly better understood thanks to the study of a 280 million-year-old fossil possessing many traits that chimaeras still maintain. This South African fossil was incredibly rare because cartilage rarely fossilizes. Often any trace of an ancient chimaera or shark is just its teeth. This fossil had many parts of the skull preserved, illustrating that this ancient fish had a similar brain shape and inner ear anatomy of modern-day chimaeras. This discovery pushes the split between sharks and chimaeras back further, as well as proves that modern chimaeras have retained many traits their primitive ancestors possessed.

Strange sex: The rat fish chimaera can either deliver sperm from its pelvis or head! It is the only vertebrate to have such a structure on its head. Model from the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

To this end, modern chimaeras really are like ghosts from ancient seas. After a large extinction 360 million years ago, cartilaginous fish sprang up all over the world’s oceans to fill in otherwise empty ecological gaps. Many of these fish were chimaeras, whose eerily-similar relatives still haunt the abyss.

Frilled Shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus)

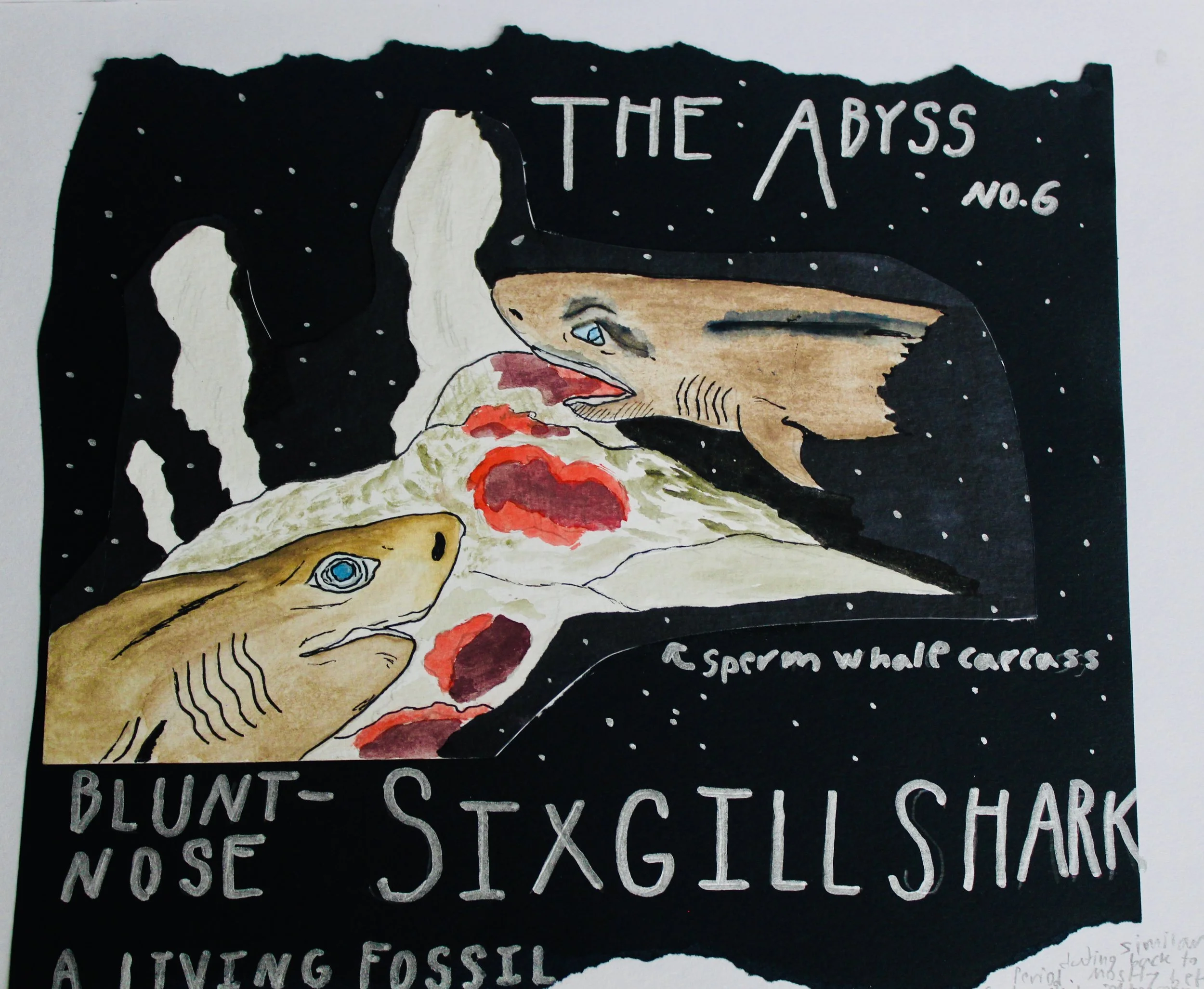

On the other side of the cartilaginous revolution some 360 million years ago are sharks. Many primitive sharks still occupy the abyss. We met one of those species, the hulking bluntnose sixgill shark, on our last voyage. Now it is time to meet possibly the most primitive member of this ancient group - the eel-like frilled shark.

The reclusive shark, named for its strange, fringed gills, has made news recently when it left the abyss to visit Japan in 2007 (the sick shark died soon afterward) and was accidentally caught off of Portugal in 2017. The first surviving description of a frilled shark dates back to 1884, and the creature’s appearance even led the examining scientist to ponder the existence of sea serpents. Its species name is latin for “consisting of snakes.”

What a strange family: An eel-like frilled shark (bottom) alongside a small tiger shark at the Melbourne Museum.

Although lacking the bulk and jaw size of the sharks that swim around our collective nightmares, the frilled shark is no less of an effective predator. It has 25 rows of backward-facing teeth that are incredibly useful for holding onto any unfortunate prey that becomes ensnared. The whiteness of the teeth even acts as a fateful beacon to the animals it shares the abyss with. Once they realize those teeth belong to a shark, it’s too late.

Maxing out at around 6 feet, a human would never be on the menu, but anything slightly smaller than the frilled shark is on the menu. The fish’s wide gape allows it to even swallow sharks up to half its size. Fossil teeth show that frilled sharks have changed very little over the last 80 million years, sticking with a lethal hunting approach that still works wonders in the dark.

Coelacanth (Latimeria)

Two ‘living fossils’ from the abyss: the coelacanth (bottom) and the elephant shark (top), a species of chimaera.

Imagine pulling up a prehistoric mosasaur, a giant swimming reptile from the age of dinosaurs, in your fishing net one day. The only glimpse people have seen of this creature are its fossils from millions of years ago, which is why everyone assumes that it went extinct with the dinosaur. The rediscovery of a prehistoric species actually occurred with a creature that shared the seas with mosasaurs for millions of years. In 1938, two worlds collided as fisherman off the east coast of Africa found themselves starring face to face with a fossil.

With a face only a mother can love, coelacanth specimens offer the ability to get face to face with prehistory. This specimen is from the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C.

It seems odd that a 6.5 foot, 200 pound fish could evade science for hundreds of years, but there are two factors that help explain the coelacanth’s disappearance and re-emergence as a “Lazarus-taxon,” or animal that has come back from the dead to science. First, the coelacanth lives up to 2,300 feet below the surface, a space less understood than some areas of the moon. One species only resides in the deep waters off of east Africa, while the other surviving species lives in Indonesia.

The second reason why coelacanths managed to fool scientists into believing they went extinct with dinosaurs is that they left scant fossil evidence between 66 million years ago and 1938. Before their disappearance from the fossil record, coelacanth’s fossils were found all over the world spanning some 300 million years! Then when the dinosaurs were wiped out, coelacanth seemingly disappeared from the fossil record. Between 66 million years ago and today is known as the coelacanth’s ghost lineage. The coelacanth did not disappear over the 60 million years, but we just have not found any of their fossils from this missing section of the coelacanth puzzle.

Above: A preserved coelacanth side-by-side with the similar fossil of its ancestor at the Natural History Museum in London.

Over the mysterious period of the coelacanth’s ghost lineage, the creature has not seemed to change very much. Several primitive features that the coelacanth still possesses are its paired lobe fins, a hinged joint in its skull to help it swallow large prey, an organ in its snout to detect prey in the dark and thick scales that are only found on other extinct fish.

The lobed fins are what really makes the coelacanth a remarkable ‘living fossil.’ They are part of the Sarcopterygii group of lobed fin fishes that gave rise to the first tetrapods to leave the water and walk on land, eventually leading to us! The coelacanth’s fins are on the end of these bony lobes. Evolutionarily, the coelacanth is one of the missing links between fish and us, which makes its rediscovery one of the landmark scientific moments of the 20th century.

As we start to ascend up, we leave this strange world seemingly stuck in the past. But the problems of today are starting to infiltrate the abyss. Isopods off of the Gulf of Mexico have been found with plastic in their guts. Deep sea fish like chimaeras, frilled sharks and coelacanths are often caught as accidental by-catch. The abyss is also warming, along with the rest of our oceans, due to climate change. These remarkable ‘living fossils’ that reside in this abyssal time capsule have survived for millions and millions of years, but even they are not safe from the destructive effects of human engineered climate change.

All photographs and artwork by Jack Tamisiea.

Sources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4uwDrdLfS4

http://mentalfloss.com/article/56278/18-awesome-facts-about-giant-isopods

https://www.popsci.com/livingartifacts/

https://mashable.com/2017/11/12/frilled-shark-portugal-discovery/?utm_cid=hp-h-1#9ovuG3OmsZq3

http://mentalfloss.com/article/60129/11-fascinating-facts-about-frilled-shark

https://www.fieldmuseum.org/blog/inside-world-elusive-vampire-squid

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5J8eTT8xvaQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8BfnZFo6S_c

https://www.fieldmuseum.org/blog/ghost-lineages

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/group/coelacanths/