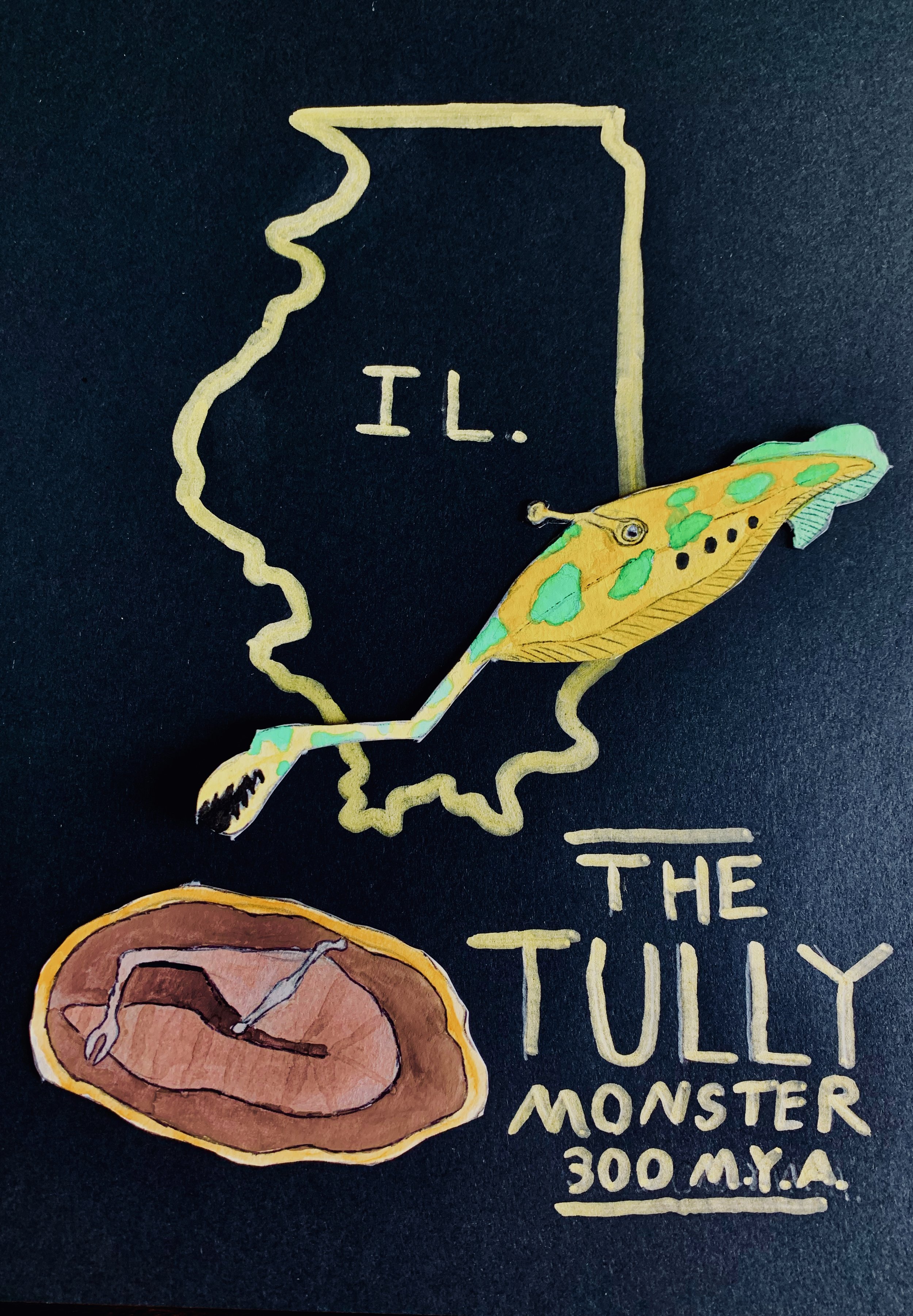

Illinois’ state fossil is bizarre … so bizarre that it took scientists decades to figure out its place in the animal kingdom.

Illinois’ state fossil is the Tully monster, perhaps the weirdest animals ever to have existed on earth!

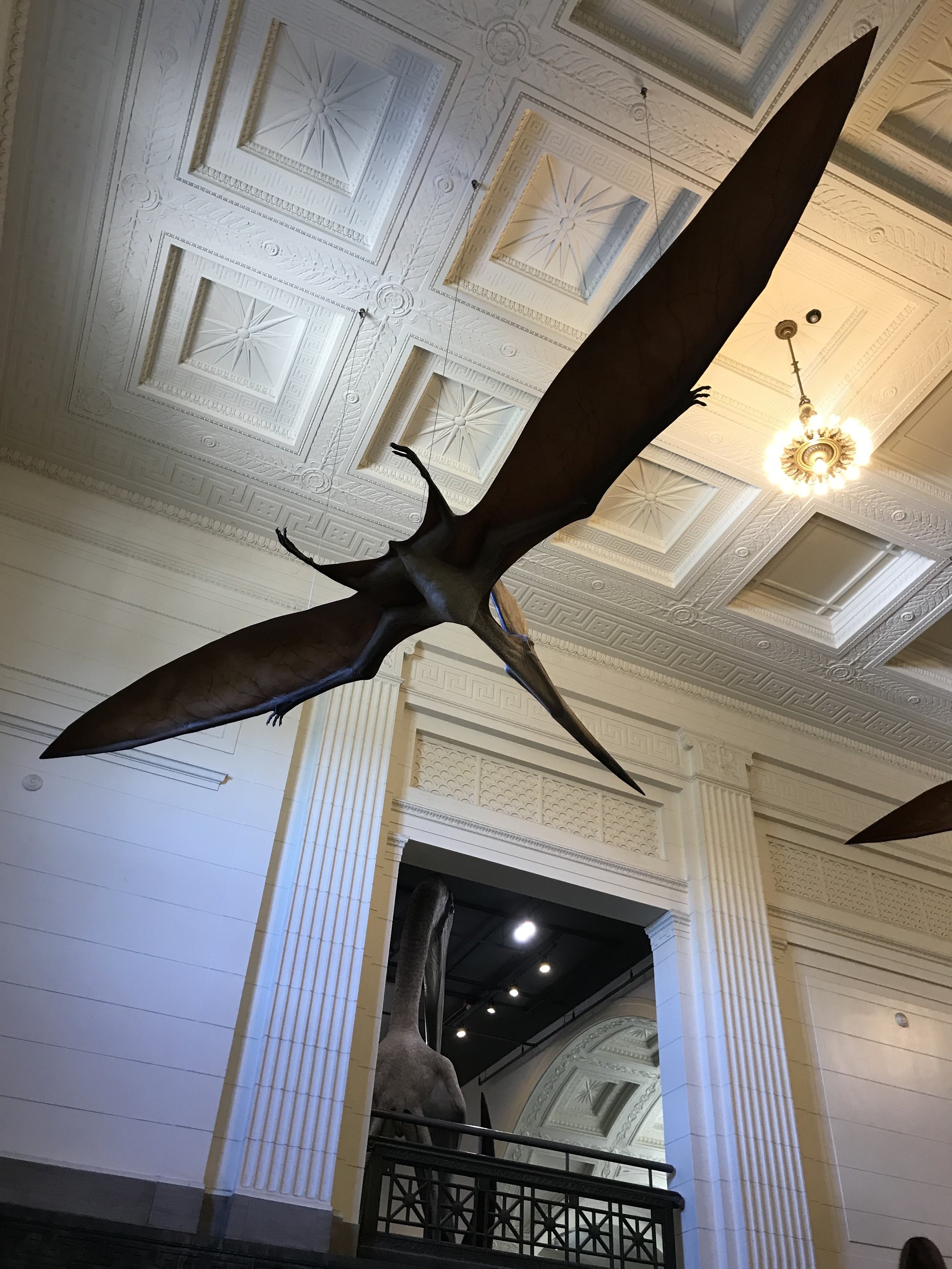

THIS WEEK IS ILLINOIS FOSSIL WEEK AT NATURAL CURIOS. OVER THE NEXT FEW DAYS, YOU’LL MEET ONE OF THE STRANGEST CREATURES TO EVER EVOLVE, GIANT, SHAGGY ELEPHANT-LIKE ANIMALS THAT ONCE STOMPED ACROSS THE STATE AND INSPIRED THOMAS JEFFERSON, AND SOME OF THE LARGEST FOSSILS IN THE WORLD THAT CURRENTLY RESIDE AT CHICAGO’S FIELD MUSEUM.

In a primordial tropical swamp, an alien monster slices through the warm water. Its eyes extend from the side of its streamlined body on long, rigid eye stalks. The creature’s mouth, studded with eight sharp teeth, is extended on a long proboscis in front of the head. It is both the first thing and the last thing this monster’s prey will ever see.

This may sound like it is taking place on Mars or one of Jupiter’s moons, but this creature once haunted Northeastern Illinois some 300 million years ago. Moreover, this creepy monster straight from the pages of a science fiction novel only maxed out at 14 inches long. Even if you fell through a time portal and landed in Grundy County, Illinois during the Pennsylvanian period, you would not have to fear the Tully monster (Tullimonstrum gregarium).

The Tully monster needs its turn on the big screen as it chases incredibly tiny time travelers through the swamps of primeval Illinois.

But if you were dropped into the Tully monster’s realm, you would indeed be in another world. During the aforementioned Pennsylvanian period, Illinois was right on the equator, smushed in the middle of the supercontinent Pangea. Much of Illinois was covered by dense forests and swamps full of primitive and strange plants that were eventually compressed into the coal we extract from Illinois today. Mazon Creek, an area known for its treasure trove of fossils from this time period, looked similar to the delta of the Amazon River. Rivers carrying the dead remnants of plants and small animals washed into the ocean here. A few pieces of this organic material sank into the muddy seafloor fossilized, eventually becoming vestiges to the deep past.

Some of these creatures serve to fill in the gaps in the evolutionary tale of the planet. Early jellyfish, squid, shrimp and even sharks are found here, providing insight into how these groups of animals have evolved over time. The Tully monster is not so helpful. Instead of illuminating secrets from this tropical, ancient Illinois, the bizarre creature only confused scientists, eluding placement in the tree of life for over sixty years. Thus, the Tully monster became an enigma trapped inside the nodule rocks of Mazon Creek, almost taunting frustrated scientists.

The Tully monster takes its name from its discoverer, Francis Tully, who discovered it in the late 1950s while fossil hunting near a coal mine. The bewildered scientists at the Field Museum, where Tully took his unusual discovery, dubbed it “Mr. Tully’s Monster” to highlight the pint-sized creature’s strange appearance. Being unique to Illinois, as well as extraordinarily weird, the Tully monster became Illinois’ state fossil in 1989 even though no one really knew what it was although theories abounded. Some scientists thought it was a segmented worms, while others thought it was a primitive marine slug. Most people could only agree on the fact that the Tully monster was an invertebrate. It had to be, right? Not quite.

A collection of Tully monsters at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

After painstakingly analyzing over 1,200 Tully monster specimens, researchers led by Victoria McCoy of the University of Leicester, who partnered with the Field Museum in Chicago, found evidence of a notochord in the enigmatic marine creature in 2016. A notochord, seen as a faint, thin line running from the creature’s snout to the tip of its tail, is a primitive structure that eventually gave rise to the spinal cord in all vertebrates, including us. It turns out the Tully monster was not a worm, or a slug, or even an invertebrate. It was one of the oldest vertebrates, finally taking its rightful place on our side of the tree of life.

McCoy’s study classifies the Tully monster in a group of jawless fish that gave rise to lampreys, who are still around in rivers today, sucking blood from unsuspecting fish with their toothy suction-cup of a mouth. Lampreys are one of the most primitive creatures with a backbone, and we now know that they came from ancient fish like the Tully monster.

With one of paleontology’s biggest mysteries solved and the Tully monster’s identity finally understood after sixty years, much still needs to be understood about the incredible creature. How did it eat and traverse its muddy environment? How did it even swim? Although some of the enigmatic creature’s mystery has been put to rest, there is still an incredible amount of questions trapped in the ancient rocks at Mazon Creek.

All artwork and photography by Jack Tamisiea.

Sources:

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature16992

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/tully-monster-mystery-solved-scientists-say/

http://isgs.illinois.edu/outreach/geology-resources/pennsylvanian-rocks-illinois

https://www.fieldmuseum.org/node/5126

https://naturalhistory2.si.edu/paleobiology/mazoncreek/